The latest Horizon Report is out – this one focused on K–12 and co-authored by the New Media Consortium (NMC) and the Consortium for School Networking (CoSN).

This year’s report is sponsored by mindSpark Learning, a non-profit that offers professional development workshops in robotics, virtual reality, coding, design thinking, makerspaces, mindfulness, “culture of innovation,” and more – many of the “key trends accelerating technology adoption in K–12 education” as listed in this year’s report. That’s not to suggest that these trends are in the report because of the sponsor; but certainly this underscores the role that the Horizon Report plays: prompting schools to buy products and services in preparation for a particular sort of technological future.

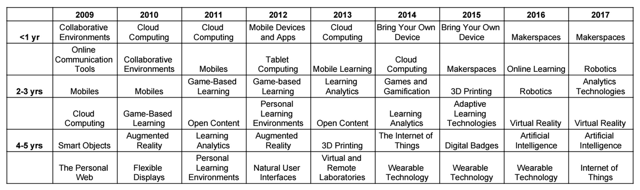

The first Horizon Report for K–12 was published in 2009, so we have 9 years now of predictions about what this technological future will supposedly entail:

I’ve long maintained that it matters less that these predictions are inaccurate – they’re always wrong in some way – than that they’re so bound up in narratives about technological inevitability and change that one can get a sense of what stories education technology’s proponents like to tell – what they wish the future holds.

This year’s report contends that,

In observing the numerous overlaps from edition to edition, it is important to note that while topics may repeatedly appear, they represent only the broad strokes of educational change; each trend, challenge, and technology development evolves over time, with fresh perspectives and new dimensions revealed every year. For example, both mobile and online learning today are not what they were yesterday. Virtual reality, chatbots, and immersive apps have added more functionality and greater potential for learning.

But this statement offers little explanation of why trends disappear and reappear from the Horizon Report other than a nod to some truism like “things move pretty fast” and “everything changes.” Have digital badges, for example – four to five years out “on the horizon” in 2015 but unmentioned in 2016 or 2017 – become mainstream or has their adoption stalled? And why? What are we meant to glean about online learning, which in 2016 was posited as less than one year out from widespread adoption? Sure, you could argue that it’s no longer “on the horizon” because online learning is ubiquitous – except, as Doug Levin recently pointed out, about 40% of US high schools do not offer any online classes at all.

In 2014, the Horizon Report began looking at some of the trends that it claims are driving technology adoption – and ideally, this should answer some of the questions about why things appear or disappear from the report. But these trends are remarkably unhelpful in doing so. According to this year’s report, we’re told, a “growing focus on measuring learning” will drive technology adoption for the next three to five years. I’d argue that’s been driving education policy (and education technology development and adoption) for about one hundred years now. In the long term – five or more years from now, the report says, “deep learning approaches” will do the same. To borrow a phrase from the theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, this is “not even wrong.”